Aerial View:

Aerial View:Also called a bird's-eye view. Observing from a point of view at a high elevation. In perspective, when the horizon line, and thus the vanishing point (-s), have been placed near or above the top of the picture frame. This applies most often to landscapes, cityscapes, etc. (Be careful not to confuse aerial view with aerial perspective.)

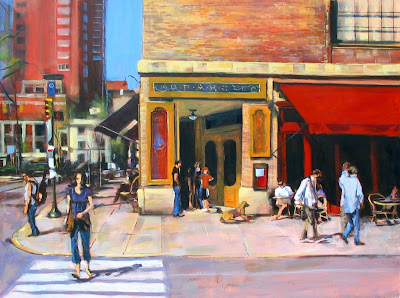

Aerial/Atmospheric Perspective:The means by which the illusion of atmospheric distance and depth is created by rendering objects in background space with less edge and value contrast. May also be accompanied by a shift from warmer to cooler hues. softer focus or lighter value.

Abstraction:The reduction or simplification of an image or object to an essential aspect (geometric or organic) of its form or content.

Axis:An imaginary straight line that indicates movement and the direction of movement.

Background:Objects or undetermined spaces surrounding the main subject of a work.

The most distant zone of space in three-dimensional illusion

Backlight:A light source positioned behind a person or object that can create a silhouette or separate the person or object from the background.

Base Tone:The darkest tone on a form, located on that part of the surface that is turned away from rays of light.

Blind Contour:Line drawings produced without looking at the paper. Such drawings are done to heighten the feeling for space and form and to improve eye-hand coordination

Cast Shadow:The shadow thrown by a form onto an adjacent or nearby surface in a direction away from the light source.

Chiaroscuro:A word borrowed from Italian ("light and shade" or "dark") referring to the modeling of volume by depicting light and shade by contrasting them boldly. This is one means of strengthening an illusion of depth on a two-dimensional surface, and was an important topic among artists of the Renaissance.

Composition:The organization and interaction of shapes, forms, lines, patterns, light and color.

Cone of Vision:The visual area represented by the drawing usually corresponding to a normal person’s vision , m i n u s t h e i r p e r i p h e r a l v i s i o n . ( a b o u t 6 0 degrees) A n g l e o f s i g h t .

Content:The subject and meaning of a work of art.

Continuous Line Drawing:

A drawing in which the implement remains in uninterrupted contact with the picture plane creating enclosed shapes.

Contour:The outline and other visible edges of a mass, figure or object.

Contour Line (Drawing):A single line that represents the edge of a form or group of forms and suggests three-dimensional quality indicating the thickness as well as height and width of the form it describes. Contour line drawing uses subtle overlapping planes.

Convergence:In linear perspective, parallel lines in nature appear to converge (come together) as they recede to a point on the Eye Level or Horizon Line. into the picture plane.

Cross-Contour Lines:Multiple, curving parallel lines running over the surface of an object horizontally and/or vertically that describe its surface qualities. Much like wire framing in 3D design.

Cross Hatching:A drawing technique to shade an object using two or more networks of parallel lines in a gradual angular progression (to achieve a build up of complex value).

Diminution:In linear perspective, the phenomenon of more distant objects appearing smaller.

Drawing:

Depiction of shapes and forms on a surface chiefly by means of lines. Color and shading may be included. A major fine art technique in itself, drawing is the basis of all pictorial representation, and an early step in most art activities. Though an integral part of most painting, drawing is generally differentiated from painting by the dominance of line over mass.

Edge:

The rim or border, the place where two things meet: the background (negative space) meets surface of objects (positive space), a “tone” or “value” meets a different tone/value.

Eye Level:

In linear perspective, the height at which the eyes are located in relation to the ground plane. Standing creates a high eye-level while sitting creates a lower one. In most views, the eye level will match a horizon line. The same as horizon line. All vanishing points in one and two point perspective are positioned on the eye level.

Figure:

The primary or positive shape in a drawing. A shape that is noticeably separated from the background. The figure is the dominant, advancing shape in a figure/ground relationship.

Figure-Ground Relationship:

An arrangement in which positive and negative shapes alternatively command attention. Also known as a positive/negative relationship.

Foreground:

The “nearest” space represented to the viewer. The “front” of the visual stage.

An exaggeration of perspective in which elements nearer to the viewer are shown much larger, and elements at a distance appear much reduced in size.

Foreshortening:

A technique for producing the illusion of an object’s extension into space by contracting its form. A way of representing a subject or an object so that it conveys the illusion of depth -- so that it seems to go back into space.

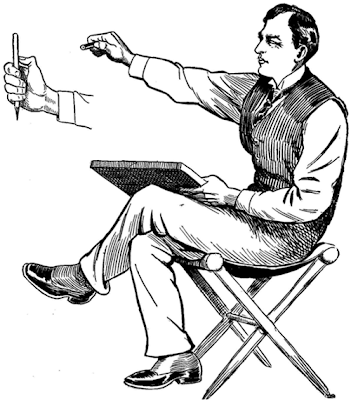

Freehand Drawing:

Drawn by hand, without the use of any mechanical device -- without the aid of a straightedge, compass, protractor, French curves, computer equipment, etc. This is the opposite of mechanical drawing.

Gestalt:

A total mental picture, or conception, of a form.

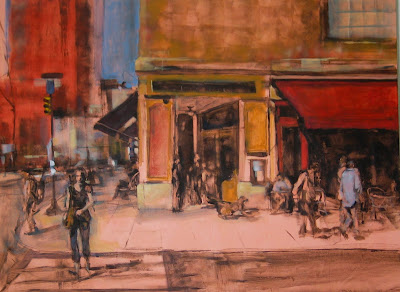

Gradation:

Any gradual transition from one tone to another. In drawing, shading through gradation can be used to suggest three-dimensional illusion.

Gesture:

A spontaneous representation of the dominant physical and expressive stance of an object. The act of making a sketch with relatively loose arm movements (gestures) -- with the large muscles of the arm, rather than with the small muscles of the hand and wrist; Or a drawing made this way.

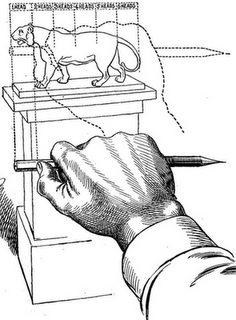

Grid:

A framework or pattern of criss-crossed or parallel lines. A lattice. When criss-crossed, lines are usually horizontal and vertical; and when lines are diagonal, they are usually at

right angles to each other.

Ground:

The actual flat surface of a drawing, synonymous with a drawing’s opaque picture plane. In a three dimensional illusion, ground also refers to the area behind an object (or figure).

Half Tone:

After the highlight and quarter tone, the next brightest area of illumination on a form. The halftone is located on that part of the surface that is parallel to the rays of light.

Highlight:

The brightest area of illumination on a form, which appears on that part of the surface most perpendicular to the light source.

Horizon Line:

In linear perspective, the line on which all vanishing points are positioned. More accurately described as the eye line or eye level.

Layout:

The placement of images within a two dimensional format.

Light Tone:

After highlight, the next light value of illumination on a form. Sometimes called indirect light.

Line:

A mark with length and direction. An element of art which refers to the continuous mark made on some surface by a moving point. Types of line include: vertical, horizontal, diagonal, straight or ruled, curved, bent, angular, thin, thick or wide, interrupted (dotted, dashed, broken, etc.), blurred or fuzzy, controlled, freehand, parallel, hatching, meandering, and spiraling. Often it defines a space, and may create an outline or contour, define a silhouette; create patterns, or movement, and the illusion of mass or volume. It may be two-dimensional (as with pencil on paper) three-dimensional (as with wire) or implied (the edge of a shape or form).

Line gesture:

A type of gesture drawing that describes interior forms, utilizing line rather than mass.

Local Value:

The basic tonality of an object’s surface. regardless of incidental lighting effects or surface texture.

Mark:

A visible trace or impression on a surface, such as a line, a dot, spot, stain, scratch, etc.

Mass:

The density or weight of an object.

Massing:

In composition: to block-in forms with the purpose of achieving an overall organization of visual weight.

Mass gesture:

A system of broad, gestural marks used to create density and weight in a form.

Middle ground:

The area between the foreground and background in a drawing.

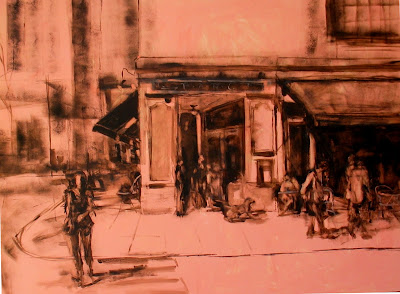

Modeled Drawing:

A method of drawing which delineates form through the use of a variety of values-A range of tones from light to dark.

Motion:

The arrangement of the parts of an image to create a sense of movement by using lines, shapes, forms, and textures that causes the eye to move over the work.

Negative Space:

The space surrounding a positive shape; sometimes referred to as a ground, empty space, field, etc.

Outline:

A line of uniform thickness, tone and speed, which serves as a boundary between a shape or form and its environment. It does not suggest contour, and is therefore flat, two dimensional. A silhouette.

Overlapping Planes:

A method of representing hierarchy of space in a drawing. Overlapping occurs when one object obscures from view part of a second object.

Planar Analysis:

A structural description of a form in which its complex curves are generalized into major planar zones.

Perspective:

Any system used to represent depth or space on a flat surface by reducing the size and placement of elements to suggest that they are further away from the viewer.

One-Point Perspective:

A frontal, head on view with a central point at eye level at which all receding parallels appear to converge and vanish.

Two-Point Perspective:

A way of representing space on the picture plane in which physically parallel elements of the same size appear progressively reduced along converging rays to the left and right, reaching a single point on the horizon on both the left and right side.

Three Point-Perspective:

A system for representing objects in space with exaggerated three dimensionality, through the use of three perpendicular sets of converging parallels.

Picture Frame:

The physical vertical and horizontal dimensions of the paper surface.

Picture Plane:

The flat, two-dimensional surface on which a drawing is made.

Plane:

Any flat level or surface.

Plastic:

Denotes the illusion of three dimensionality or movement into the picture plane as it relates to the flat, two-dimensional nature of the picture plane itself. We refer to this as plastic space in contrast to perspective space.

Positive Space:

The shape of an object that serves as the subject for a drawing. The relationship between positive shape and negative space is sometimes called figure/ground, foreground/background relationship.

Proportion:

A term that refers to the “accurate” relationship of part to part in a realistic drawing. It can also refer to the expressive purposes, e.g. Distortion of proportion to consciously or unconsciously achieve a subjective intention. Proportion also relates to a sense of balance.

Reflective Light:

The relatively weak light that bounces off a nearby surface onto the shadowed side of a form.

Relative Scale:

A way in which to represent and judge the spatial position of an object in three-dimensional illusionistic space so that forms drawn smaller appear further away and forms that are drawn larger appear closer.

Representational:

A drawing that attempts to achieve a near-likeness to the objects being drawn. Drawings which strive to achieve the qualities of realism.

Rendering:

A depiction or an interpretation. Also, a drawing in perspective of a proposed structure. (Rendering can be used either as a noun or as a verb.)

Scale:

A ratio or proportion used in determining the dimensional relationship between a representation to that which it represents (its actual size), such as maps, building plans, and models.

Shallow Space:

A relatively flat space, having weight and width but limited depth.

Shape:

A contained, edged-in area on the two-dimensional surface. Or an area that suggests containment. A shape is always interdependent with another element (shape or space) in the composition.

Sighting:

The visual measurements of objects and spaces between objects.

Silhouette:

Any dark two-dimensional shape seen against a light background.

Sketch:

A quick drawing that loosely captures the appearance or action of a place or situation. Sketches are often done in preparation for larger, more detailed works of art.

Space:

The distance between images or points in a drawing. We contain space when defining edges of interrelated shapes.

Station Point:

In linear perspective, the fixed position a person occupies in relation to the subject that is being drawn.

Surface:

The actual physical structure or texture of the drawing paper containing degrees of smoothness, gloss, or roughness.

Texture:

The actual or suggestive surface quality of a two-dimensional shape or three-dimensional volume. Texture can be created by using skillful drawing techniques, erasure, rubbing, or employing specific materials such as sand.

Two Dimensional Space:

The flat, actual surface area of a drawing, which is the product of the length times the width of the drawing paper support.

Three Dimensional Space:

The actual space in the environment, and the representation of it in the form of pictorial illusion.

Value:

Black, white and the gradations of gray tones between them. The relative degree of light and dark.

Value Relativity:

The changing visual identity of values in juxtaposition, sometimes called value contrast.

Value Scale:

The gradual range from white through gray to black.

Value Pattern:

The arrangement or organization of values that control compositional movement and create a unifying effect throughout a work of art.

Visual Weight:

The potential of any element or area of a drawing to attract the eye.

Volume:

The overall size of an object, and by extension the quantity of three-dimensional space it occupies.